Click to learn more about author Thomas Frisendal.

I recently (finally) had the opportunity to read Doug Laney’s fine book about Infonomics. I have followed his work on this for years, because we share the ambition that data and information should be recognized as assets, just like factory equipment and trucks. Because data keep the economy going.

Infonomics – The Financial Side of the Information Economy

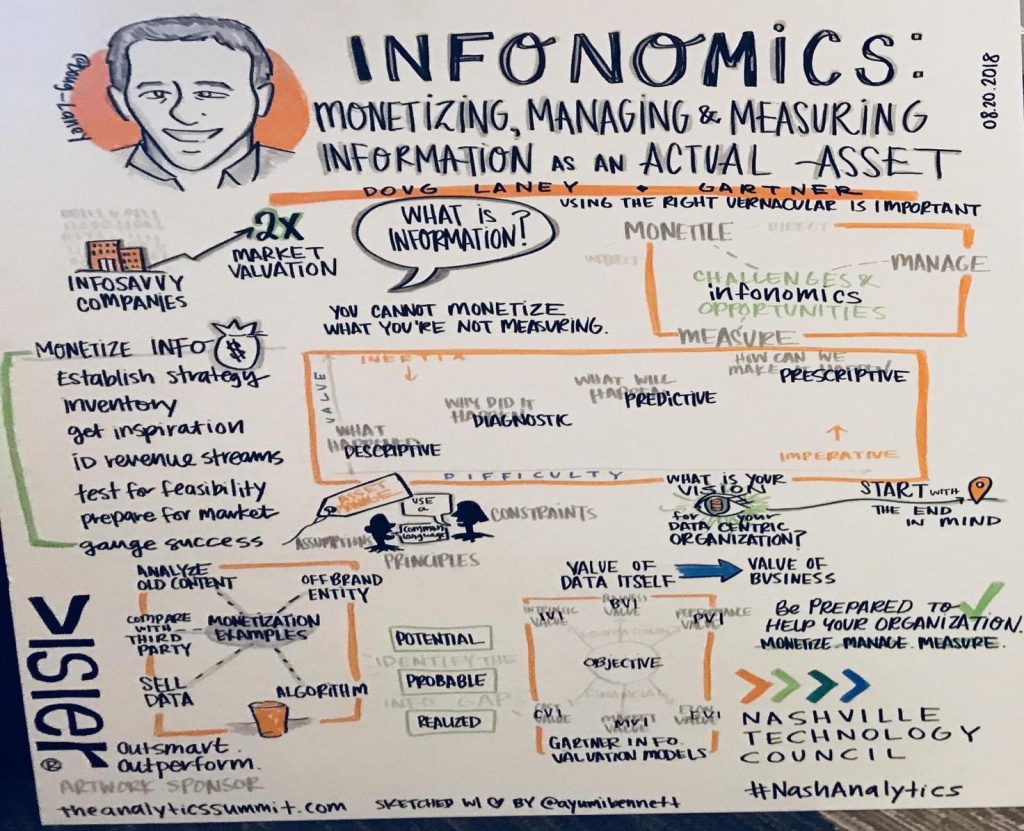

Infonomics s an important concept, that Doug Laney has coined and refined over the last 10 years or so. And I am with him all the way. In his book he carefully (and well researched) follows the path from data to measuring data over monetizing the data to establish information as a source of income. Big Data seen from a financial perspective. This fine drawing (by Ayumi Bennett) summarizes Doug’s keynote from the Analytics Summit in Nashville earlier this year:

(A larger version of the above can be found on Doug Laney’s LinkedIn pages)

Recommendation: If your company have opportunities for monetizing information (and many have) you should not hesitate to read Doug’s advise in the book. It is indeed the authoritative guideline available for working with Data Science and so forth with an enterprise financial perspective.

But, Hey, There is an Intangible Issue!

Doug also brings the annoying dilemma of valuation of assets to the forefront. Even given the fact that data is driving a larger and larger part of the economy, information is – in accounting contexts – not assets. Except for in a few situations such as for instance mergers and acquisitions, where it is accepted practice to assign a value to assets such as customer lists (which is very much just data).

In the so-called Conceptual Framework being developed by the accounting standards bodies IAS and IFRS an asset is defined as:

“A resource controlled by the enterprise as a result of past events and from which future economic benefits are expected to flow to the enterprise.”

This is an asset:

(https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Horizontal_Bagging_Hay_Baler_VTKT-W90.jpg)

This asset is a tangible asset. It consists of mechanical parts, which are controlled by an embedded computer (PLC), and operates according to developed software. It can count the number of bales processed. It is on the balance sheet. Its value is an estimated resale price. If it stops working, the owner will have to buy a new one.

But:

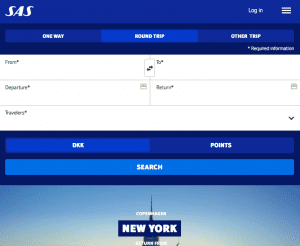

This is a SAS Airlines online sales point. It is an intangible asset. It consists of software parts, a database and a data model, which are controlled by a number of computers, and it operates according to developed software. It is not on the balance sheet. If it stops working, SAS immediately looses revenue, but chances of failure are negligible. Furthermore, it can not only count the number of tickets sold, it can also generate valuable information about customer profiles and behavior. This information is used in marketing programs together with partners offering loyal SAS customers interesting offers on select items, based on the customer activities, I presume. Such monetization is possible because of the presumably well scoped and designed data model of the booking system behind this.

Is This Debate Just a Kind of Chasing Windmills?

No – computer resident information is running business. In June and July 2017 the company Maersk Line, which is the world’s largest container shipping company, was attacked by a cyber / hacker attack. This is part of the summary in Danish newspaper Jyllands-Posten on Feb. 15, 2018 (https://bit.ly/2yCtVqi, translated from Danish):

“The attack started 27 June 2017. The virus came in via the back door in a piece of Ukrainian software and spread rapidly to the container business Maersk Line, it’s port business APM Terminal and its logistics business Damco. The virus was known under the name NotPetya. The computers and software went out of operation. Maersk’s container ports all over the world stood still, and many offices could not call.”

In the company’s annual report for 2017, the company stated:

“In June, A.P. Moller – Maersk was hit by a cyber-attack that was one of the most aggressive that we and our global partners have ever experienced. The effect on profitability was USD 250-300 million, with the vast majority of the impact related to Maersk Line in Q3.”

“Virtual, cyber-based, electronic” attacks on day-to-day operational information is indeed vital to company operations. This is a very tangible event. Somebody attacked some information on some servers, and cost this company hundreds of millions of dollars.

In my own interpretation of financial logic, this does indeed mean that the value of the company’s equity in reality was reduced by way of demolishing an otherwise intangible asset.

Tangible or Intangible – The Accounting Way

An intangible asset is described as:

“An intangible asset is an identifiable non-monetary asset without physical substance”.

“Identifiable” means the asset is either:

- “… capable of being separated or divided from the entity and sold, transferred. Licensed, rented or exchanged…. Or”

- arises from contractual or other legal rights …”

The IFRS (International Financial Reporting Standards) exemplifies intangible assets as for example: trademarks, domain names, customer lists, customer contracts, customer relationships, artistic assets (literary works etc.), licensing agreements, broadcast rights, patented or un-patented technology, computer software, databases and trade secrets, among many more.

An entity (company) is required to recognize as an asset something, which is identifiable and:

- It is probable that the expected future benefits that are attributable to the asset will flow to the entity, and

- The cost of the asset can be measured reliably.

This is an important and ongoing discussion in the accounting standardization committees such as IASB and FASB, and has been so for quite some years. Doug documents the issues, but there is no consensus as of yet. So in order for information assets to make inroads into for instance the US Generally Accepted Accounting Practises (GAAP) some definitions and rules must be reworked and additional provisions must be taken.

Much is founded in the notion of “intangible assets” meaning that information (for example) cannot be valuated, because it is not physical and may be copied without hindrance (which cannot be said about tangible assets such as a Ferrari).

How to measure the contribution of information to the benefits of the company, and how to measure the costs of developing them? Either in the sense of IT development and/or in the sense of R & D? However, in both cases, the prescription today is accounting for them as costs at development time, except for special cases such as acquisitions and commercially developed information products. What disturbs the eye in this setup is that the benefits occur later and there is really no link between them and the cost of producing the platform (data + data models), which together “materialize” the information.

Maybe the problem arose because of the context of accounting?

Accounting and its Consumers

Let us step back and try to answer the question of what the purpose of accounting is?

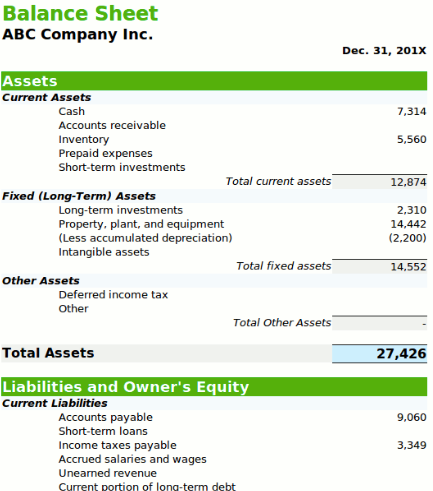

Here follows a part of a fictive balance sheet:

(By Aishakassimkassim1996 [CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)], from Wikimedia Commons)

Who are interested in balance sheets? Traditionally there are different consumers of accounting information and annual reports:

- Managers of the company

- Shareholders (wanting to know the results of their investments)

- Potential investors (considering investing in the company)

- Employees (wondering about the future)

- The public, including the gentlemen of the Press, politicians and so forth

Obviously there is a mixture of vested interests. Some of them are close to being operational, but some are also of longer term interest.

Take potential investors, for example. They are interested not only in financial results over time, but they could also take (due diligence style) looks at some of the assets:

- Established governance of processes, such as ISO 9000?

- Age and skills of the employees?

- Age and stability (failure rates) of equipment

- Adaption of new technologies (in technology driven businesses, and who are not, these days)?

But being intangible, the value of the information assets are generally not to be found in the balance sheet. This in spite of the fact that the company might make fortunes out of them (think Facebook, Google etc.). Much data “comes for free”, or are part of an exchange economy (you give us your personal data and we will give you better services, if you don’t mind that we sell parts of your data to third parties).

Information “Creation” is in most cases very likely accounted for as part of “Software Development” (under the IT budget).

The GAAP’s FASB Topic “ASC 350-40 Accounting for Internal-use software” explains in detail how software internally developed should be capitalized. PWC provides a good, short overview here.

I think that the discourse generally is missing an important dimension.

What Makes Data Become Information?

Yes, I am a data modeler, so to me it is obvious that the secret sauce that morphs data into information is: the data model! Without a communicable description of structure and meaning, data is just alphabet soup with lots of indigestible numbers.

Maybe this is the missing information that the accountants don’t see (because they don’t look for it)? In a sense they are correct that raw data does not provide much value. But described data in well-structured models keep some of todays biggest companies alive and kicking. Ehm, yes, quite well, thank you. If you ask me, it was to be expected that companies such as Facebook develops something like GraphQL, which provides a well-structured representation of data underlying the business models of the company.

Frisendal’s law: No data model, no asset – it is as simple as that.

Let me attack it in another line of arguments. How do you “manufacture” high-value information?

Well, today you might think of manufacturing as a generalization of 3D printing. A 3D printer certainly requires a model (a data representation of something to become a physical part). Can such a model be patented or become a trade secret? I cannot see why not.

Similarly: If you want to “manufacture” valuable information, you must have a good (potentially patentable or protectable) data model.

Returning to our wise investor from up above, he or she would be looking for evidence of a high-quality data model before making a decision about investing in the data-driven company. And investors reward “infocentric” organizations. In Doug Laney’s word:

“… We (at Gartner, my note) identified businesses that demonstrate information centric traits …. Then we compared their (information savvy companies, my note) market-to-book value … to the S&P average to discover that infocentric companies not only demonstrate a slight ability to generate more shareholder value per asset, but also have a 200-300% higher q value than the norm. In addition to that eye-opener, we found that information product companies (i.e. those in the business of selling data) have a 400-500% higher Tobin’s q than average.”

(Note: Tobin’s q compares market value and asset values).

Where to Look Today?

By todays accounting standards (GAAP and IFRS, for example), data models are, most likely costed as direct expenses in (research) and SW development. Part of the IT budget, right?

As an aside, this is not the case for companies actually developing and selling data models as part of their SQ products. But that is another discussion.

If you look at the 10-K filings (yearly reports to the Securities and Exchange Commission) of US companies, (and Doug Laney has done that, mentioned in his blog, there seems to be a connection between mentions of information and data related topics and the subsequent increases in operating profits (as compared to the company’s industry).

A lot of work is spent on these 10-K filings comments by the management and the auditors. Here is a clipping from one of the large IT companies:

“… On an ongoing basis, we evaluate our estimates, including those related to the accounts receivable and sales allowances, fair values of financial instruments, intangible assets and goodwill, useful lives of intangible assets and property and equipment, income taxes, and contingent liabilities, among others. We base our estimates on historical experience and on various other assumptions that are believed to be reasonable, the results of which form the basis for making judgments about the carrying values of assets and liabilities.” (The underlining is done by me, see the full 10-K filing here.)

It seems that purchased, and to some extent developed, technology are subject to amortization schemes of their “fair value” over a “life” of amortization over, say, 10-12 years. Whether the data models are in that category in this 10-K filing is not specified. And is Data Modeling development of “technology”? I would say so, since it is about creating the interpretation of the data (the interface to all downstream processes).

So, how can I get a clear understanding of the state of, and future development costs of, the company’s data models?

“Data Exposure” as a Balance Sheet Note?

Let me propose that we create a “balance sheet” friendly metaphor for valuation of the data model as an intangible asset? (Just as a short to mid-term compromise while we wait for accounting standards to catch up).

In the financial sector one of the larger kind of worries is “exposure”. How much does the company rely on the GBP rate? Or how large is our exposure in the Euro zone?

By epSos.de [CC BY 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0)], via Wikimedia Commons

Similarly, we need to understand the importance of the data model to the operations and profitability of the company. Allow me to propose a calculation of the impact of the data model on the potential market value of the company, calculated as a percentage of the amount of revenue, which is in risk, should it happen that the data model is / becomes faulty, unoperational or needs to be changed significantly. Just a percentage, that’s all. Or A, B, C, D or similar.

You may call it “Frisendal’s q” (just kidding!). Let us call it “data exposure”?

I would expect a peanut farmer (no pun intended) to score low, and I would expect Google, Facebook and many similar companies to score highest.

On top of that there are issues about volume, quality, lifetime expectancies, type (proprietary or not) and also the penetration of Data Governance.

I am sure that both regulators (like the US SEC and their colleagues) and the leading auditing companies can formulate how to report these things in manners similar to the balance sheet comments found in the US 10-K Filings and their likes around the world.

Let me suggest a pragmatic approach for a new section in the balance sheets comments:

This is a whole lot better than nothing, if you ask me.

And it is all I want for Christmas!